In discussion with another writer over coffee, I found myself explaining biases in the artificial intelligences – particularly large language models – as something that is recent. Knowledge has been subject to this for millenia.

Libraries have long been considered our centers of knowledge. They have existed for millenia and have served as places of stored knowledge for as long, attracting all manner of knowledge to their shelves.

Yet there is a part of the library, even the modern library, which we don’t hear as much about. The power of what is in the collection.

‘Strict examination’ of library volumes was a euphemism for state censorship

Like any good autocrat, Augustus didn’t refrain from violent intimidation, and when it came to ensuring that the contents of his libraries aligned with imperial opinion, he need not have looked beyond his own playbook for inspiration. When the works of the orator/historian Titus Labienus and the rhetor Cassius Severus provoked his contempt, they were condemned to the eternal misfortune of damnatio memoriae, and their books were burned by order of the state. Not even potential sacrilege could thwart Augustus’ ire when he ‘committed to the flames’ more than 2,000 Greek and Latin prophetic volumes, preserving only the Sibylline oracles, though even those were subject to ‘strict examination’ before they could be placed within the Temple of Apollo. And he limited and suppressed publication of senatorial proceedings in the acta diurna, set up by Julius Caesar in public spaces throughout the city as a sort of ‘daily report’; though of course, it was prudent to maintain the acta themselves as an excellent means of propaganda.

“The Great Libraries of Rome“, Fabio Fernandes, Aeon.com, 4 August 2023

Of course, the ‘editing’ of a library is a difficult task, with ‘fake news’ and other things potentially propagating through human knowledge. We say that history is written by the victors, and to a great extent this is true. Spend longer than an hour on the Internet and you may well find something that should be condemned to flame, or at least you’ll think so. I may even agree. The control of information has historically been central, and nothing has changed in this regard. Those who control the information control how people perceive the world we live in.

There’s a fine line between censorship and keeping bad information out of a knowledge base. What is ‘bad’ is subjective. The flat earth ‘theory’, which has gained prominence in recent years, is simply not possible to defend if one looks at the facts in entirety. The very idea that the moon could appear as it does on a flat earth would have us re-examine a lot of science. It doesn’t make sense, so where is the harm in letting people read about it? There isn’t, really, and is simply a reflection on how we have moved to such heights of literacy and such lows of critical thought.

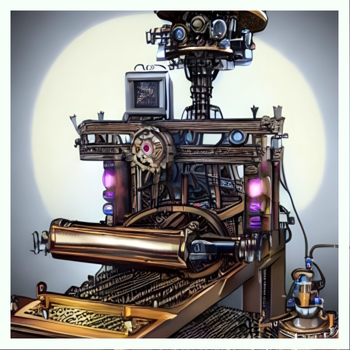

The answer at one time was the printing press, where ideas could be spread more quickly than the manual labor, as loving as it might have been, of copying books. Then came radio, then came television, then came the Internet – all of which have suffered the same issues and even created new ones.

What gets shared? What doesn’t? Who decides?

This is the world we have created artificial intelligences in, and these biases feed the biases of large language models. Who decides what goes into their training models? Who decides what isn’t?

Slowly and quietly, the memory of damnation memoriae glows like a hot ember, the ever present problem with any form of knowledge collection.