I was about to write up a history of my interactions with the music industry as far as ownership over at RealityFragments.com, and I was thinking about how far back my love for music went in my soundtrack of life. This always draws me back to “The Entertainer” by Scott Joplin as a starting point.

I could use one of the public domain images of Scott Joplin, someone I have grown to know a bit about, but they didn’t capture the spirit of the music.

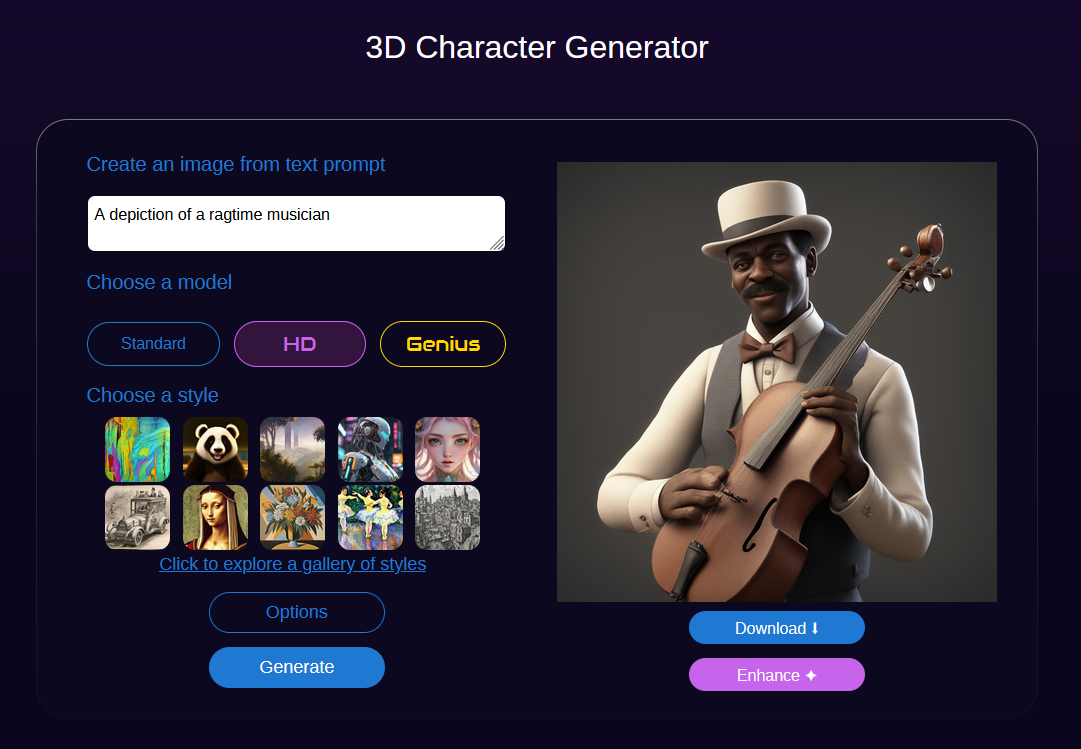

I figured that I’d see what DALL-E could put together on it, and gave it a pretty challenging prompt in it’s knowledge of Pop Culture.

As you can see, it got the spirit of things. But there’s something wrong other than the misspelling of “Entertainer”. A lot of people won’t get this because a lot of people don’t know much about Scott Joplin, and if they were to learn from this, they’d get something wrong that might upset a large segment of the world population.

I doubled down to see if this was just a meta-level mistake because of a flaw in algorithm somewhere.

Well, what’s wrong with this? It claims to be reflecting the era and occupation of a ragtime musician, yet ragtime music came from the a specific community in the United States that are called African-Americans now, in the late 19th century.

That would mean that a depiction of a ragtime musician would be more pigmented. Maybe it’s a hiccough, right? 2 in a row? Let’s go for 3.

Well, that’s 3. I imagined they’d get hip-hop right, and it seems like they did, even with a person of European descent in one.

So where did this bias come from? I’m betting that it’s the learning model. I can’t test that, but I can go just do a quick check with DeepAI.org.

Sure, it’s not the same starting prompt, but it’s the same general sort of prompt.

Let’s try again.

Well, there’s definitely something different. Something maybe you can figure out.

For some reason, ChatGPT is racebending ragtime musicians, and I have no idea why.

There’s no transparency in any of these learning models or algorithms. The majority of the algorithms wouldn’t make much sense to most people on the planet, but the learning models definitely would.

Even if we had control over the learning models, we don’t have control over what we collectively recorded over the millennia and made it into some form of digital representation. There are implicit biases in our histories, our cultures, and our Internet because of who has access to what, who shares what, and these artificial intelligences using that information based only on our biases of past and present determines the biases of the future.

I’m not sure Scott Joplin would appreciate being whitewashed. Being someone respected, of his pigmentation, in his period, being the son of a former slave, I suspect he might have been proud of who he became despite the biases of the period.

Anyway, this is a pretty good example of how artificial intelligence bias can impact the future when kids are doing their homework with large language models. It’s a problem that isn’t going away, and in a world that is increasingly becoming a mixing pot beyond social constructs of yesteryear, this particular example is a little disturbing.

I’m not saying it’s conscious. Most biases aren’t. It’s hard to say it doesn’t exist, though.

I’ll leave you with The Entertainer, complete with clips from 1977, where they got something pretty important right.

From Wikipedia, accessed on February 1st 2024:

Although he was penniless and disappointed at the end of his life, Joplin set the standard for ragtime compositions and played a key role in the development of ragtime music. And as a pioneer composer and performer, he helped pave the way for young black artists to reach American audiences of all races.

It seems like the least we could do is get him right in artificial intelligences.