One of the underlying concepts of Artificial Intelligence, as the name suggests, is intelligence. A definition of intelligence that fits this bit of writing is from a John Hopkins Q&A:

“…Intelligence can be defined as the ability to solve complex problems or make decisions with outcomes benefiting the actor, and has evolved in lifeforms to adapt to diverse environments for their survival and reproduction. For animals, problem-solving and decision-making are functions of their nervous systems, including the brain, so intelligence is closely related to the nervous system…”

“Q&A – What Is Intelligence?“, Daeyeol Lee PhD, as quoted by Annika Weder, 5 October 2020.

This definition fits well, because in all the stuff about different writings related to different kinds of intelligences and human intelligence itself, the words of Arthur C. Clarke echo.

I’m not saying that what he wrote is right as much as it should make us think. He was good about making people think. The definition of intelligence above actually stands Clarke’s quote on it’s head because it ties intelligence to survival. In fact, if we are going to really discuss intelligence, the only sort of intelligence that matter is related to survival. It’s not about the individual as much as the species.

We only talk about intelligence in other ways because of our society, the education system, and it’s largely self-referential in those regards. Someone who can solve complex physics equations might be in a tribe in the Amazon right now, but if they can’t hunt or add value to their tribe, all of that intelligence – as high as some might think it is – means nothing. Their tribe might think of that person as the tribal idiot.

It’s about adapting and survival. This is important because of a paper that I read last week that gave me pause about the value-laden history of intelligence that causes the discussion of intelligence to fold in on itself:

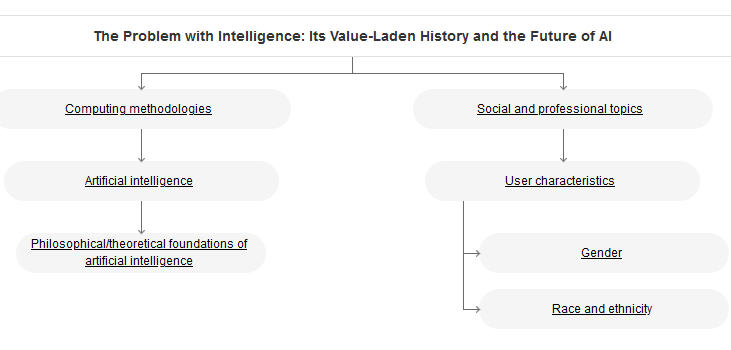

“This paper argues that the concept of intelligence is highly value-laden in ways that impact on the field of AI and debates about its risks and opportunities. This value-ladenness stems from the historical use of the concept of intelligence in the legitimation of dominance hierarchies. The paper first provides a

“The Problem with Intelligence: Its Value-Laden History and the Future of AI” (Abstract), Stephen Cave, Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence University of Cambridge, 07 February 2020.

brief overview of the history of this usage, looking at the role of intelligence in patriarchy, the logic of colonialism and scientific racism. It then highlights five ways in which this ideological

legacy might be interacting with debates about AI and its risks and opportunities: 1) how some aspects of the AI debate perpetuate the fetishization of intelligence; 2) how the fetishization of intelligence impacts on diversity in the technology industry; 3) how certain hopes for AI perpetuate notions of technology and the mastery of nature; 4) how the association of intelligence with the professional class misdirects concerns about AI; and 5) how the equation of intelligence and dominance fosters fears of superintelligence. This paper therefore takes a first step in bringing together the literature on

intelligence testing, eugenics and colonialism from a range of disciplines with that on the ethics and societal impact of AI.”

It’s a thought provoking read, and one with some basis, citing examples from what should be considered the dark ages of society that still perpetuate within modern civilization in various ways. One image can encapsulate much of the paper:

The history of how intelligence has been used, and even become an ideology, has deep roots that go back in the West as far back as Plato. It’s little wonder that there is apparent rebellion against intelligence in modern society.

I’ll encourage people to read the paper itself – it has been cited numerous times. It lead me to questions about how this will impact learning models, since much that is out there inherits much of the value laden history demonstrated in the paper.

When we talk about intelligence of any sort, what exactly are we talking about? And when we discuss artificial intelligence, what man-made parts should we take with a grain of salt?

If the thought doesn’t bother you, maybe it should, because the only real intelligence that seems to matter is related to survival – and using intelligence ideologically is about the survival of those that prosper in the systems impacted by the ideology of intelligence – which includes billionaires, these days.